What is Site 9?

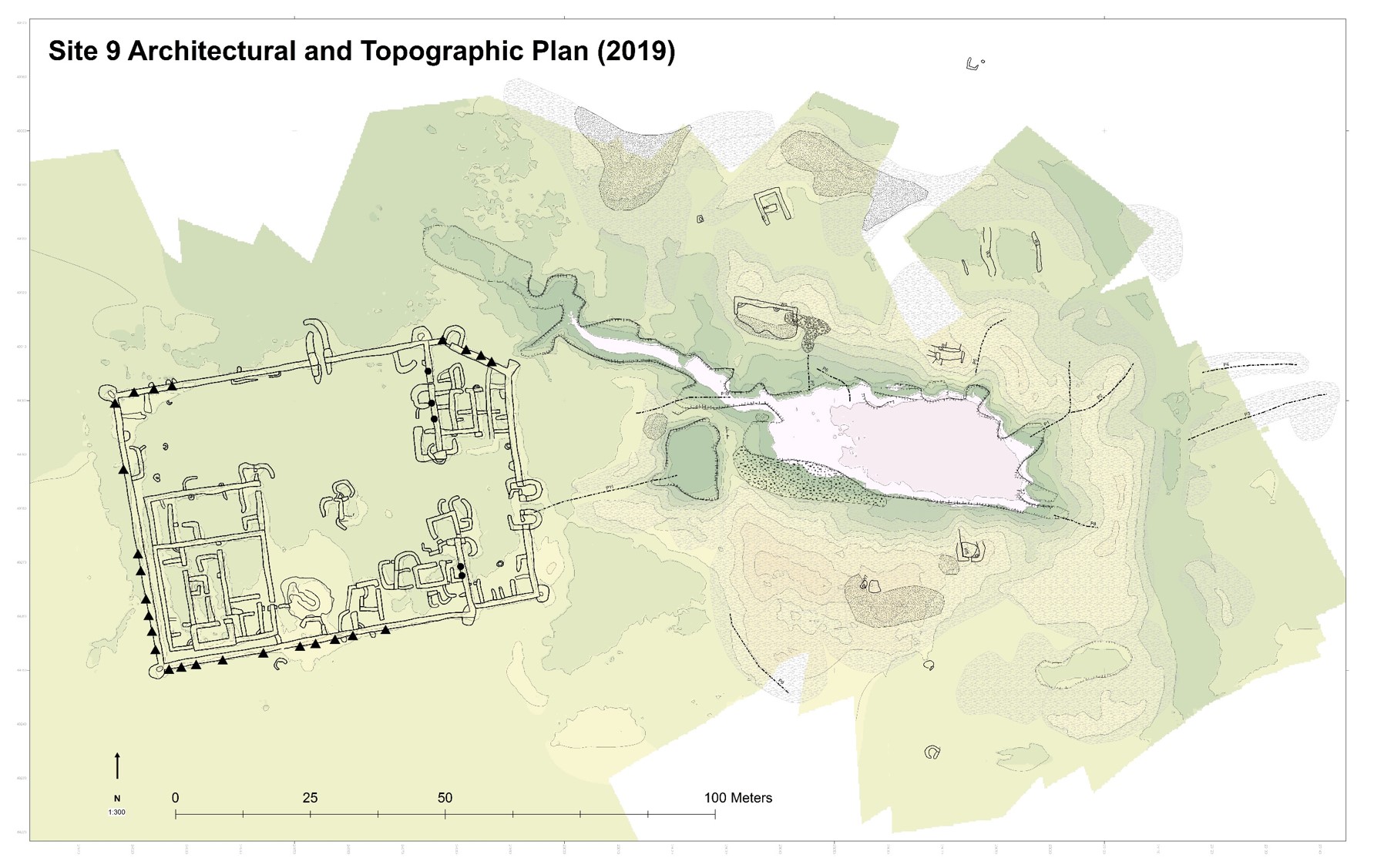

The best known site at Wadi el-Hudi was named “Site 9” by Ahmed Fakhry. It dates to the Middle Kingdom (c. 2000 to 1700 BCE) and was likely founded during the reign of Senwosret I. It includes a rectangular settlement, amethyst mine, and areas for refining amethyst in the middle of a flat wadi bed. Walls in the settlement were constructed from small stacked boulders taken locally from the site’s surface and from the debris of the mining operations.

The settlement includes three major structural sections, which Ian Shaw labelled Areas A, B, and C. Area A in the southwest corner consists of two extremely well-constructed buildings that may have acted as housing, administrative, and storage areas for high officials. Area B is on the eastern side of the settlement and was an extension that was built onto Site 9 by a later expedition that reused the site. Based on its plan, Area B was an administrative storage area, which we hope to investigate in a future season. Area C is mostly an open court with small structures in the middle of the settlement; these were likely utilitarian, multi-purposed areas. There is evidence that stelae (inscribed stones) had once been present at Site 9.

Ahmed Fakhry discovered a few stelae there that he transported to the Aswan Museum. Because no natural large boulders exist at Site 9 on which to carve inscriptions, inscriptions would have been only on free standing stelae. Since they would have been visible and portable, these have disappeared over the last 4000 years or been brought to museums during the last century.

What is Site 5?

Site 5 consists of a large settlement, amethyst mine, and amethyst refinement area that dates to the Middle Kingdom (c. 2000 to 1700 BCE). It was first founded during the reign of Montuhotep IV, but it too was reused by later expeditions. We are in the process of studying the archaeology to investigate how it was reused, renovated, and expanded over time. This investigation will likely reveal multiple phases of the site’s use and restructuring during the Middle Kingdom.

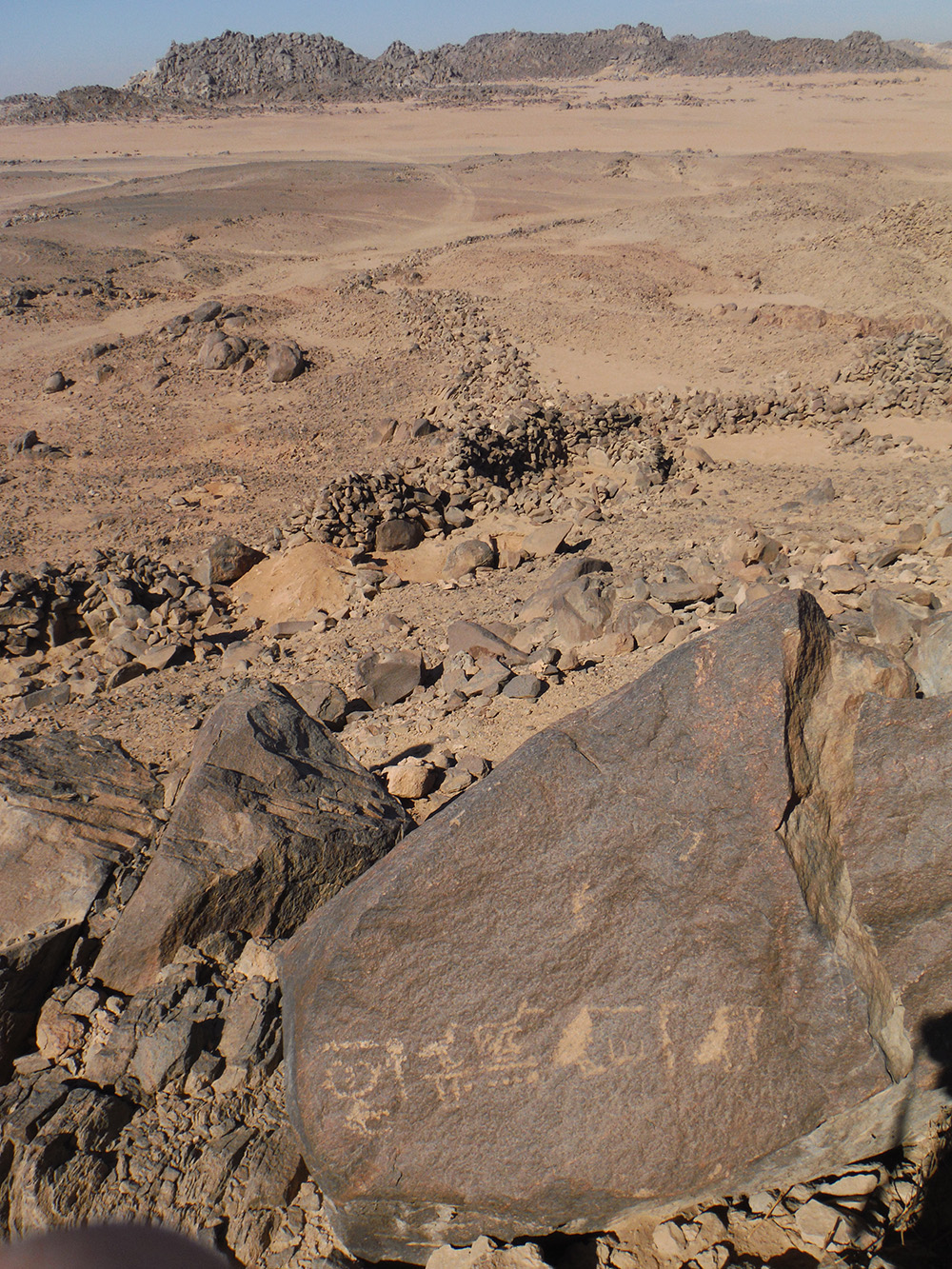

Unlike Site 9, the Site 5 settlement was built on top of a hill, and its designers incorporated the natural landscape and boulders into the structure of the settlement to give it an extra level of protection. For example, parts of the enclosure walls follow natural high ridges so that a 2 meter high wall actually looked higher to an observer approaching from down-slope. Similarly, naturally occurring huge boulders were used as gateways or walls and floors of various rooms. Unlike any other known settlement in ancient Egypt, Site 5 includes a double enclosure wall. We still need to examine this in more detail, but it seems like the exterior enclosure wall protected everything within the settlement, including housing areas for the workers. Then an interior enclosure wall divided the workers’ housing areas from administrative and storage areas located on the highest part of the hill. Because enormous boulders lay all over Site 5, they were convenient surfaces for people to carve inscriptions. Over 100 inscriptions still exist across Site 5 as testimonials of the people who lived there.

What is Site 6?

Site 6 is located on top of a high mountain next to Site 5. From this vantage point, a person can see for kilometers in all directions, and one has clear sightlines to Sites 4, 5, and 9, among others. In the Middle Kingdom (c. 2000 to 1700 BCE), this area was a military post where soldiers sat for hours watching below. In their boredom, they drew over one hundred inscriptions around this peak, in one place making a vast “inscription panel.” Their carvings include the names, titles, and images of soldiers, as well as their dogs, weapons, sandals, and more. However, they were not the first people to inscribe these rocks. About 1000 years earlier the terrain was more hospitable to pastoral nomads wandering the desert to feed their herds. A few of those pastoral nomads carved their images and pictures of cattle and ibexes onto these rocks (c. 3000 BCE). Interestingly, the Middle Kingdom soldiers incorporated some of these older rock carvings into their own inscriptions. For example, one Middle Kingdom soldier drew himself stabbing a cow that was drawn 1000 years earlier.

What is Site 4?

Site 4 is a vast archaeological site first discovered by Ahmed Fakhry, but not visited by any later researchers until the work of the Wadi el-Hudi Expedition. It is a settlement nestled in the valley between two tall hills and an amethyst mine. Although it was reused by multiple mining expeditions, it was inhabited during two distinct periods.

It was first built and used extensively during the Middle Kingdom (2000 to 1700 BCE), but then expeditions during the Ptolemaic and Roman Periods (1st century BCE to 1st century CE), thoroughly renovated and reused the site. Archaeological levels clearly distinguish the temporal phases. As at Site 9, almost no naturally occurring boulders jut out of the ground at Site 4. Consequently, any large inscriptions needed to be carved onto free standing stelae. Both Ahmed Fakhry and the Wadi el-Hudi Expedition have discovered about 20 stelae or their fragments at Site 4 dating to the Middle and New Kingdoms. There may have once been many more, but they disappeared over the site’s 4000 year history, even being reused during the Ptolemaic and Roman phases.

The main administrative and storage areas are located in the Central Blocks on the valley floor. Among other things, we have found several ostraca (broken pieces of pottery with notes written on them) as well as seals and seal impressions (small stones that administrators used to impress their insignia onto mud attached to a box, letter, or bag). These artifacts point to a vigilant administration overseeing the mining operations.

What is Site 8?

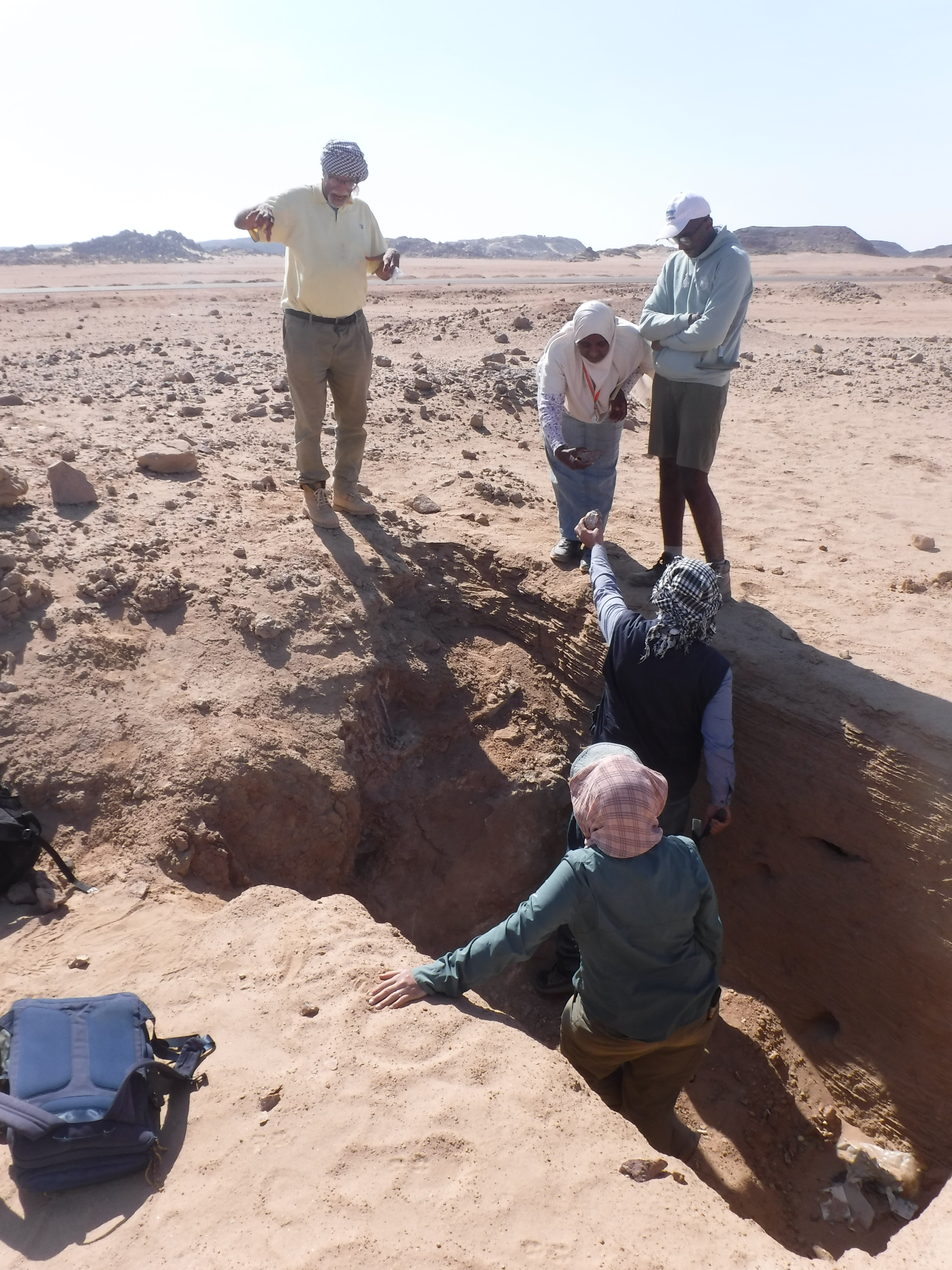

Ahmed Fakhry’s team originally identified Site 8 in 1952[i], and it was visited again briefly by Ian Shaw and Robert Jameson in 1992.[ii] It is the closest site to Aswan located on a sandy plain between granite hills. Originally, Fakhry identified Site 8 as likely the location for a well. But, after having studied the surface and excavated there, we disagree with that identification. In antiquity, three medium-sized holes were dug in this area, which we believe were mines, rather than wells. Their spoil heaps make a large pile in the center of the site and about 10 large huts were later built onto the sides of the mound. Remains from the Middle Kingdom, Ptolemaic, and Roman Periods occur here, including an uninscribed Middle Kingdom, round-top stela and base. A preliminary test trench was dug into one of these holes in 2021 to reveal very narrow horizontal levels of sand created by thousands of years of rain events. According to Geologist Dr. Mohamed Hamdan of Cairo University,[iii] the hole could not have been a well because of the evenness of the horizontal striations; if it were a well, the water moving at the bottom would have created a rippling in these levels. Plus, we found pieces of milk quartz. Evidence in support of a well was also lacking; there is no stairway or handholds to access the bottom of the well, nor are there broken water jars. Our quest to find any ancient water sources at Wadi el-Hudi thus continues, but as of now the most likely scenario is that constant supply caravans were necessary to bring food and water to the mining expeditions from the Nile valley.

[i] Fakhry, A. The Inscriptions of the Amethyst Quarries at Wadi El Hudi. Cairo: Government Press, 1952.

[ii] Shaw, I, and R. Jameson. “Amethyst Mining in the Eastern Desert: A Preliminary Survey at Wadi El-Hudi.” Journal of Egyptian Archaeology 79 (1993): 81-97.

[iii] Personal communication.

What are Sites 11 and 12?

Sites 11 and 12 were originally identified by Ahmed Fakhry in 1952.[i] Site 12 is at the base of a steep cliff nestled into a hidden valley. In that valley, small groups of people returned several times over hundreds or thousands of years to mine at a small scale, including during the Middle Kingdom, Persian Period, and Greco-Roman Periods. It is unclear what mineral was mined here; however, amethyst is the most likely candidate because the site is on the same geological line as other amethyst mines and because no gold mining querns were found in the area. But modern gold mining occurred on the other side of the mountain behind Site 12, and likely during the Islamic Period as well (Sites 20 and 46). At Site 12, spoil heaps, rock shelters, and archaeological remains irregularly dot the landscape. At an unknown point in time, a wall was built around the mine on three sides. In places, it was built on top of older spoil heaps. The wall also displays several different building styles every few meters, suggesting that multiple people worked to build it. Because of the steep cliff surrounding Site 12, heavy though sporadic rainstorms in the desert have created torrents of water that rushed into the abandoned mine. The abandoned mine, therefore, might unintentionally have become a water source in the desert on occasion.

Site 11 overlooks Site 12 from a high, but close-by mountain peak. The settlement’s walls take the shape of the sloped mountainside with steep paths leading up the interior sides of the settlement walls. It was a short-lived settlement, but represents a rare site from the Persian Period in the Eastern Desert. It is likely that an expedition mined nearby for a limited amount of time during the Achaemenid Persian rule over Egypt. Site 11’s fortified settlement might also tie into a larger, temporary Persian presence at Wadi el-Hudi at the same time. A few Persian Period amphorae were found at Site 5, and on the surface of the Horus Stela (WH143) from Site 6, seven Aramaic graffiti attest to Persians being at Wadi el-Hudi in 476 BCE.[ii]

We were able to make preliminary observations and maps of Sites 11 and 12 in 2016. Unfortunately, both illegal and legal miners have since claimed the area, and much of the archaeological evidence has been destroyed just in the last few years.

[i] Fakhry 1952.

[ii] B. Porten and A. Yardeni. Textbook of Aramaic Documents from Ancient Egypt. Winona Lake, Eisenbrauns, 1999, pp. 281-284, D22.46-51.

What are Sites 13 and 14?

Sites 13 and 14 were originally mentioned by Ahmed Fakhry in 1952. Site 14 was an ancient gold mine used since the Islamic Period. It was visited by traveler Hansjoachim von der Esch in the late 1930s and studied briefly by Rosemarie and Deitrich Klemm in 1993.[i] Currently, a modern gold mining company is continuing operations and the medieval mine is now gone. In antiquity, miners working at Site 14 brought their ore to Site 13 for processing, which is a half kilometer away. Site 13 is on an enormous sandstone outcrop with natural shelters created by caves and spaces within the rocks. Its perimeter is over 1.5 km long with the sandstone ridges creating multiple levels of occupation. Hundreds of spaces and hundreds of thousands of artifacts related to occupation and medieval gold processing are cluttered all over the area, suggesting that there was once a dense town here that must have been related to an organized effort to produce gold. Early Arabic inscriptions, Nebi Samweil pottery imported from Syria-Palestine, and hundreds of diorite querns and other tools are scattered across the site. This settlement likely relates to a time in the 9th and 10th centuries when organized gold mining operations in Aswan arose and increased mining production in the Eastern Desert.

In addition to gold processing, Site 13 is important for two other reasons. First, it was likely a stop on a camel caravan route leading from the desert and Red Sea coast through Wadi el-Hudi into the Wadi Abu Aggag and thence to Aswan. Camel walking lines are still visible in the satellite imagery of the wadi, and three images of camels appear as rock art on the western side of the sandstone outcrop, next to the wadi. Second, Site 13 was an important early human habitation area during the Middle Paleolithic Period, as evidenced by an immensely important and dense level of Paleolithic tools and byproducts. In the Paleolithic Period, it is likely that water ran through the watercourse of Wadi el-Hudi making these natural sandstone caves ideal shelters for early man on a savannah-like plain, much more favorable than in the ancient Egyptian Period or today.

[i] Fakhry 1952; von der Esch, H. Weenak – Die Karawane Ruft, Leipzig, F.A. Brockhaus, 1941; Klemm, R. and D. Klemm. Gold and Gold Mining in Ancient Egypt and Nubia, Munich, Springer, 2013.

What is Site 21?

Site 21 is a Middle Nubian, amethyst mining settlement contemporary to the Egyptian Middle Kingdom. The large Ancient Egyptian expeditions were not the only people mining in the Eastern Desert during the Middle Kingdom (circa 2000-1700 BCE). Small groups of other people also carried out small-scale mining as we see at Site 21. Although it is likely that the people working at Site 21 were there at the same time as the large Egyptian expeditions, they did not interact with them because the artifacts corpora do not overlap and there are no paths between the sites. Site 21 shows that the amethyst mining in Wadi el-Hudi extended to groups of people previously not accounted for by the hieroglyphic inscriptions that have been documented from the region.

Site 21 is located on a large sandy and rocky plain on which people built 13 dry-stone features. Four of them are large huts that are typically about 2-3 meters wide by a meter high, with associated courtyards and windbreaks. These features are very distantly spaced out over the landscape, often standing 50 meters away from the next feature. On the northern side of Site 21, there is the well-preserved Feature 11, which we excavated in 2023. This dates from the late 11th to mid 12th dynasties. Interestingly, about 80% of the pottery we found here is Middle Nubian. The pottery is similar in decoration, clay-fabric recipe, and forming technology to that of the C-Group, but it also has distinct differences. For example, some of the Nubian pots were made from desert clays. This fact implies that the potters who made them gathered clay from desert sources and may have spent much of their lives in the desert. That is to say, the people associated with these pots may have been local Nubians living at least part-time in the desert. The miners with these Nubian-style pots also ate and drank from a few Egyptian-style pots. The miners likely came back to Site 21 to mine multiple times over several years. They kept their living space quite organized, perhaps sleeping in the hut, processing raw amethyst on the porch in front of the hut, and cooking in a space slightly downslope.

Other small groups of people also came to Site 21 to mine too. Our excavation of Feature 4/5 at the southern part of Site 21 demonstrates that mining continued at the site during the late 12th or 13th dynasties. The people living in the set of huts here used mostly Egyptian pottery, with smaller quantities of Middle Nubian ceramics.

What is Site 51?

When we came across Site 51 in January 2023, we thought we were the first to discover it because it is not mentioned by Ahmed Fakhry or others. But we were soon surprised to learn about its actual discovery in the 1930s! Site 51 was first visited by German explorer and diplomat, Hansjoachim von der Esch, as he records in his travelogue Weenak – die Karawane ruft. When an unexpected sandstorm rose up, he and his team of Bishareen guides took refuge at Site 51 for two days and noted its abundant inscribed petroglyphs. In fact, they may have been the same people who carved two Arabic inscriptions there dated to 1938. However, they were by no means the first people to live there.

Site 51 is a sandstone rock face in the northeastern part of the main desert path through Wadi el-Hudi. The sandstone creates natural caverns that are perfect resting spots while in the Eastern Desert. One of these natural caves is about 8×10 meters wide and a meter high. It is quite cool inside even during incredibly hot weather. A space in between these rocks also creates a natural water seep where rainwater may gather. Site 51 seems to be a place where pastoral nomads stayed for weeks or months at a time while herding their animals through the desert. This place was used off-and-on for thousands of years, as seen by a thick level of archaeological disposition. Pottery primarily dates to the Islamic Period, but earlier pottery, including handmade, Middle Nubian pottery was found on the surface. Over fifty rock inscriptions occur in every nook and crevice. Most of them are images of animals, including animals being herded, cattle, ibexes, and more. However, there is also a First Intermediate Period or early Middle Kingdom inscription mentioning an Egyptian explorer. And there are four sets of tally marks; thus, people living here were counting something. While the pastoral nomads stayed here, they spent much of their time grinding various products onto the sandstone rock. Dozens of grinding slicks and grinding stones of various sizes and shapes occur all over the site.

What is Dihmit South?

Dihmit South is perhaps the largest Middle Kingdom fortified settlement and mining complex located in the desert to the southeast of Aswan. James Harrell and Robert Mittelstadt first discovered it in 2013,[i] and in January 2023, we became the first archaeological team to do a preliminary survey of the region. Dihmit South is remarkably similar to Wadi el-Hudi’s Sites 5 and 9, so much so that the same administrators, workers, and supply line transporters may have facilitated all of these places. The majority of Dihmit South’s occupation occurred throughout the entire Middle Kingdom, including into the 13th dynasty. However, there is also evidence for low-levels of occupation or short term visitation during the New Kingdom, Ptolemaic and Roman Periods, and Islamic Periods.

The main Middle Kingdom fortified settlement of Dihmit South covers an area over 100m x 60m. The dry-stone architecture was built in four different phases, with the earliest and tallest walls still standing to three meters high. Seven bastions reinforce the walls, and small windows look through those bastions. The settlement show several phases of rebuilding, including blocked doors and blocked windows. The settlement can be divided into four major areas and two large courtyards. There are several distinct architectural units with their own homogenous structures. An Area that we have labelled “A” in reference to its similarly to Wadi el-Hudi Site 9 seems to be the more protected, administrative area that bisects the settlement and restricts access to the entire eastern portion. Inside of Area A, there are several rooms that have thick deposits of chipped quartz, including dozens of pieces of amethyst still visible on the surface. There are also two paths that lead from this room, through the settlement’s gates directly toward the mines. Moreover, an inscription of User-Montu dating to the reign of Senwosret I[ii] mentions that they came to Dihmit to mine ḥsmn, “amethyst.” Because of this room’s thick deposition, the presence of amethyst, and the inscription, it is likely that Dihmit South was constructed to facilitate amethyst mining. Thus, Wadi el-Hudi is no longer known as the only Middle Kingdom amethyst mining region.

To the south of Dihmit, there are two enormous mines, two medium sized mines, and other soundings. The large mines have well constructed paths leading into them that are wide enough for workers to pass each other, carrying loads of rocks and dirt out. Over a dozen small buildings or windbreaks surround the larger mining zone where the first level of mineral processing took place. A small building littered with tools is also located near the mines where people likely fixed tools or baskets for the workers when they were broken.

On the top of the north hill, overlooking Dihmit South is a double saddle hillcrest where nearly 30 cairns, a cairn-court, and 6 standing rocks were built. We also discovered three stelae written by officials here. There are so many cairns, that this area seems to be constructed with more than a purely navigational or surveillance purpose in mind. By comparison to other Middle Kingdom mining settlements like Stelae Ridge at Gebel el-Asr,[iii] it is possible to conclude that this cairn-covered hill was perhaps created for religious practice. Additionally, paths, huts, cairns, and more archaeological phenomena can be seen in all directions. The various features we have been able to observe both in person and remotely show that Dihmit South was likely the center of a vast network of mining sites in the Middle Kingdom.

[i] Harrell, J. and R. Mittelstaedt. “Newly Discovered Middle Kingdom Forts in Lower Nubia.” Sudan & Nubia 19 (2015): 30-39.

[ii] Harrell and Mittelstadt 2015, 37.

[iii] Pethen, H. “The Stelae Ridge Cairns: A Reassessment of Archaeological Evidence” in Proceedings of the XI International Congress of Egyptologists, ed. Rosati and Guidoitti, 2017: 485-490.